Bridging the Gap: A Multi-Stage Approach for Company Name Matching

Recently, I had to deal with a problem that seemed trivial, but then spiralled into a multi-month headache. The below blog post explains the problem and will hopefully save someone else the same pain I went through.

The main dataset I am working with comes from an employer review website where employees can leave anonymous reviews for their current or past employer. In order to bring in other variables on the firms, I wanted to match the firms in my review dataset with an official source. For Switzerland, this was the Zefix registry. Germany does not have a publicly available firm registry, so I used the Orbis dataset. This is paywalled, but accessible through some university libraries.

The main issue was that I had was that the user-inputted company names had:

Typos

Misspecification (e.g. using the brand name instead of the legal entity)

Wilful errors (e.g. some users preferred to write something like “XXX” instead of the actual company name)

Inclusion of irrelevant information (e.g. ABC GmbH Zurich instead of just ABC GmbH)

Connecting messy, user-generated strings to a pristine official registry is a complex challenge, especially when dealing with corporate entities. For example, even if the user-inputted string is clean and reads “ABC GmbH”, it is not clear if this should be liked to “ABC Holdings GmbH”, “ABC Manufacturing GmbH”, “ABC International GmbH”, or “ABC Schweiz GmbH”. The main issue is that much of my later analysis relies on the accuracy of these matches, so my priority is quality over quantity.

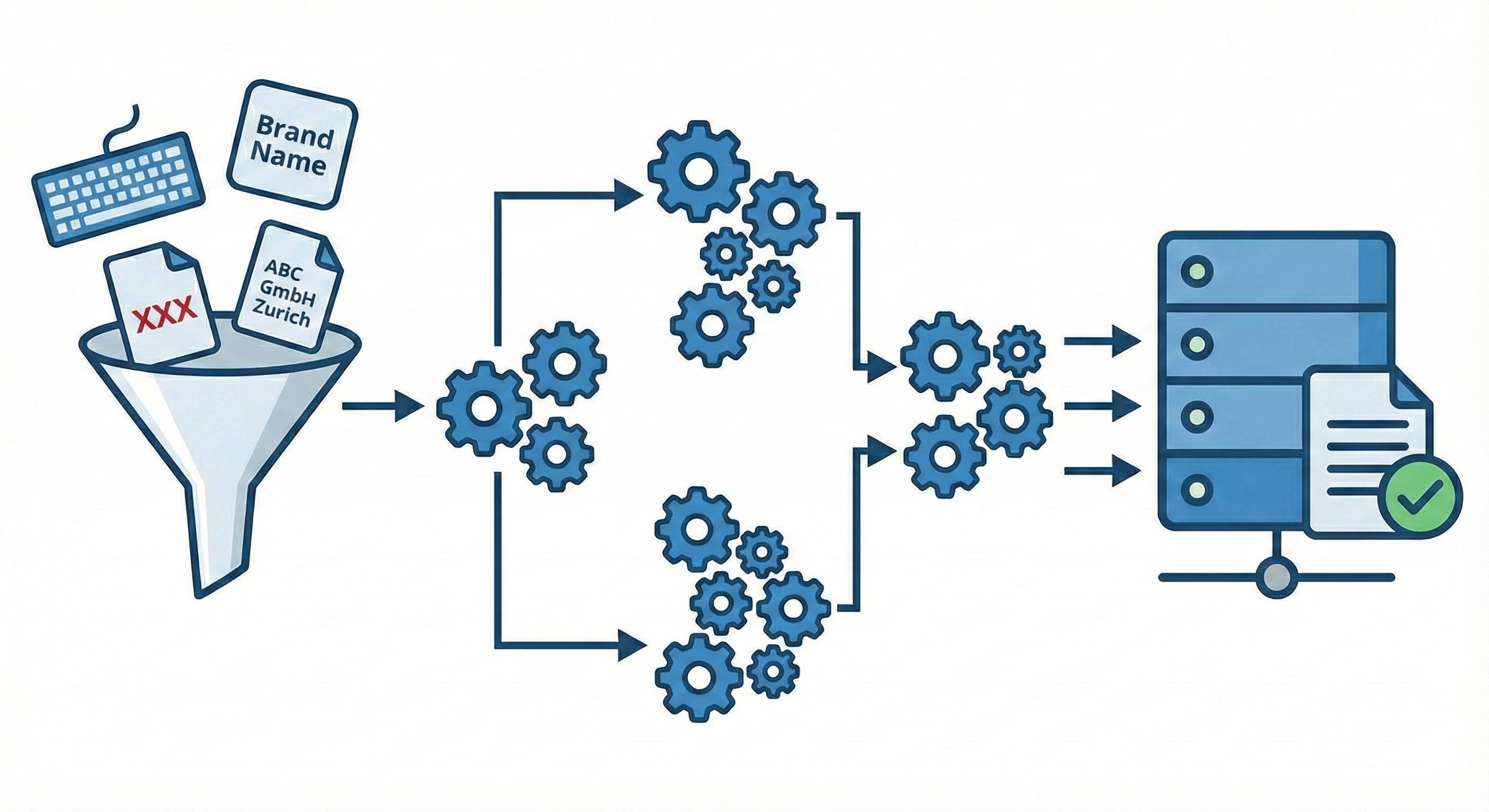

This post breaks down the architecture of a robust R-based pipeline designed to match employer names from a large-scale user-inputted Query Set to an official registry. The pipeline employs a “waterfall” strategy—moving from strict to loose matching techniques—and culminates in a Large Language Model (LLM) verification step.

The Challenge: Why Simple Fuzzy Matching Is Not Enough

A common mistake in this type of string matching is relying solely on simple string distance metrics like Levenshtein or Jaro-Winkler. While useful, these metrics fail when faced with the semantic variability of corporate names. For example:

Legal Form Noise: “Alpha Consulting” vs. “Alpha Consulting Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung”.

Word Reordering: “Berlin Bakery” vs. “Bakery Berlin”.

Subsidiary Complexity: “Global Corp Germany” vs. “Global Corp International Ltd.”

Abbreviations: “B.M.W.” vs. “Bayerische Motoren Werke”.

To solve this, I built a pipeline that treats matching not as a single step, but as a filtration process.

Phase 1: The Foundation — Normalization

Before any matching can occur, the data in the query set and the register must be reasonably similar. The pipeline begins by loading the “dirty” query data and the “clean” reference data.

Intelligent Normalization

The core of this phase is a custom normalization function. Standardizing company names requires more than just lowercasing strings. The pipeline applies a rigorous cleaning protocol specifically tuned for the German (DACH) market, though the logic applies globally:

Transliteration: Special characters and umlauts are standardized (e.g., “Müller” becomes “mueller”). This handles encoding errors that often creep into user-generated content.

Legal Form Canonicalization: Long-form legal structures are converted to abbreviations (e.g., “Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung” $\rightarrow$ “gmbh”). Later, these suffixes are stripped entirely for fuzzy matching.

Noise Removal: Stop words (“and”, “und”, “et”), geography (e.g., “Deutschland”, “Switzerland”), and punctuation are stripped away.

Deduplicating the Reference

The Orbis database often contains multiple entries for the same firm (branches, subsidiaries, historical records). Matching against a duplicate-riddled database creates chaos.

The script deduplicates the reference data by creating a “priority score” for every entity. If multiple records share the same normalized name, I keep the one with:

The highest number of employees.

The highest operating turnover.

The presence of valid industry codes.

The presence of valid location codes.

This ensures that if I match a company, I am linking it to its most economically significant record.

Phase 2: The Waterfall Matching Strategy

I use a “waterfall” approach to balance precision and computational cost. I attempt the cheapest, most accurate methods first, removing matched companies from the pool before attempting more expensive fuzzy methods.

1. The Exact Match

The first pass is a simple inner join on the normalized names. If the cleaned query name is identical to the cleaned reference name, it is flagged as a “Perfect” match. This creates a high-confidence baseline and typically resolves 60% of the dataset instantly.

2. Fuzzy Matching with Blocking (zoomerjoin)

For the remaining unmatched queries, calculating the distance between every query and every reference row ($N \times M$ complexity) is impossible with millions of rows.

We use the zoomerjoin library to perform high-speed fuzzy joining using blocking techniques:

Blocking: The data is partitioned. We might only compare companies starting with the same two letters.

Q-grams: Strings are broken into tri-grams (sequences of 3 characters).

Jaccard Similarity: We measure the overlap of these tri-grams.

Candidates that pass a threshold are then scored with the Jaro-Winkler distance, with the best candidate returned. The threshold here can be adjusted to allow fewer or more matches. Given the LLM verification step at the end, the threshold here is set relatively loosely.

3. Full-Text Search (SQLite FTS5)

String distance metrics struggle when words are reordered or when a query is a substring of the target (e.g., “Siemens” vs. “Siemens Healthcare”). To solve this, the script utilizes SQLite’s FTS5 (Full-Text Search) engine.

Indexing: Build a high-performance search index of the registry data.

Token-Based Retrieval:Execute parallelized SQL queries. This finds matches based on the presence of tokens rather than the sequence of characters.

Validation: Results returned by the search engine are double-checked with string distance metrics to ensure they aren’t just sharing common words like “Services” or “GmbH”.

4. Probabilistic Matching (MatchMakeR)

The final automated stage uses the MatchMakeR library. This approach is sophisticated because it weighs tokens by rarity (Inverse Document Frequency).

Matching on the word “Solutions” adds very little to the match score because thousands of companies have that word.

Matching on a unique name like “Infineon” adds a massive score.

This helps identify companies that share unique identifiers even if the rest of the string is noisy or different.

5. Manual Overrides

Finally, a “Manual” dictionary is applied. This handles edge cases known to break algorithms—usually large conglomerates with colloquial names (e.g., mapping “BMW” to its specific legal entity “Bayerische Motoren Werke AG”) or companies that trade under completely different brand names than their legal entities. This is only used for unmatched firms that have many reviews (i.e. where the marginal benefit of matching them by hand is relatively high).

Phase 3: LLM Post-Processing

Automated fuzzy matching inevitably produces false positives. A string distance of 0.9 might look good mathematically but be semantically wrong (e.g., “Austrian Airlines” vs. “Australian Airlines”—only two letters differ, but they are different entities).

To solve this, the pipeline includes a secondary script acting as an AI Judge.

Azure OpenAI Integration

The script iterates through the “Fuzzy” and “Probabilistic” matches in steps 2, 3, and 4 above (skipping the high-confidence Perfect matches) and sends them to an Azure OpenAI (GPT-4) endpoint.

The Expert Persona

The prompt is important here. We do not just ask “Are these the same?”. The system is instructed to act as a corporate registry expert. It is given the query name and the matched Orbis candidate (or cluster of candidates). It evaluates the match based on specific rules:

Legal Entity Hierarchy: It understands that a subsidiary often matches the parent group for the purpose of analysis.

Legal Forms: It knows that differences in suffix (GmbH vs AG) are often irrelevant for identity.

Nuance: It distinguishes between simple typos and completely different companies.

Robust Engineering: The Chunking Strategy

LLM APIs can be slow, expensive, and prone to timeouts. Processing thousands of rows requires a robust architecture. This script checked 300,000 pairs of companies and had a runtime of around fifty-five hours. The script uses a chunking Strategy:

Batching: Work is broken into small batches.

Checkpointing: Results are written to disk immediately after every batch.

Resumability: If the script crashes or the internet cuts out, you simply re-run it. It detects which chunks already exist and resumes exactly where it left off.

Conclusion

By layering exact matching, vector-based fuzzy matching, full-text search, and Large Language Model verification, I achieve a result that is both high-volume and high-accuracy. This approach allows me to process datasets that were previously too messy or too large to handle manually, ensuring reliable data for downstream economic analysis.

Code

All code can be accessed at the firmmatchr Github repository.